SOCIAL BASED ART text by Kym Maxwell, 2013 (research images below)

As an artist I have explored notions of play in public space and social constructivist theories through sculpture design. I have devised the GOODWILL project to challenge notions of spatial and social politics, the role of spectatorship and to question the importance and (decline) of kinesthetic play in our lives. The GOODWILL KIT is integral in this aim, as provocateur. It established the potential for the projects physical manifestation as a sculpture, but also as a means in which to engage in dialogue about the importance of un-fetted or unsupervised play and the subsequent building of narratives that ensues when we tinker, and open our minds.

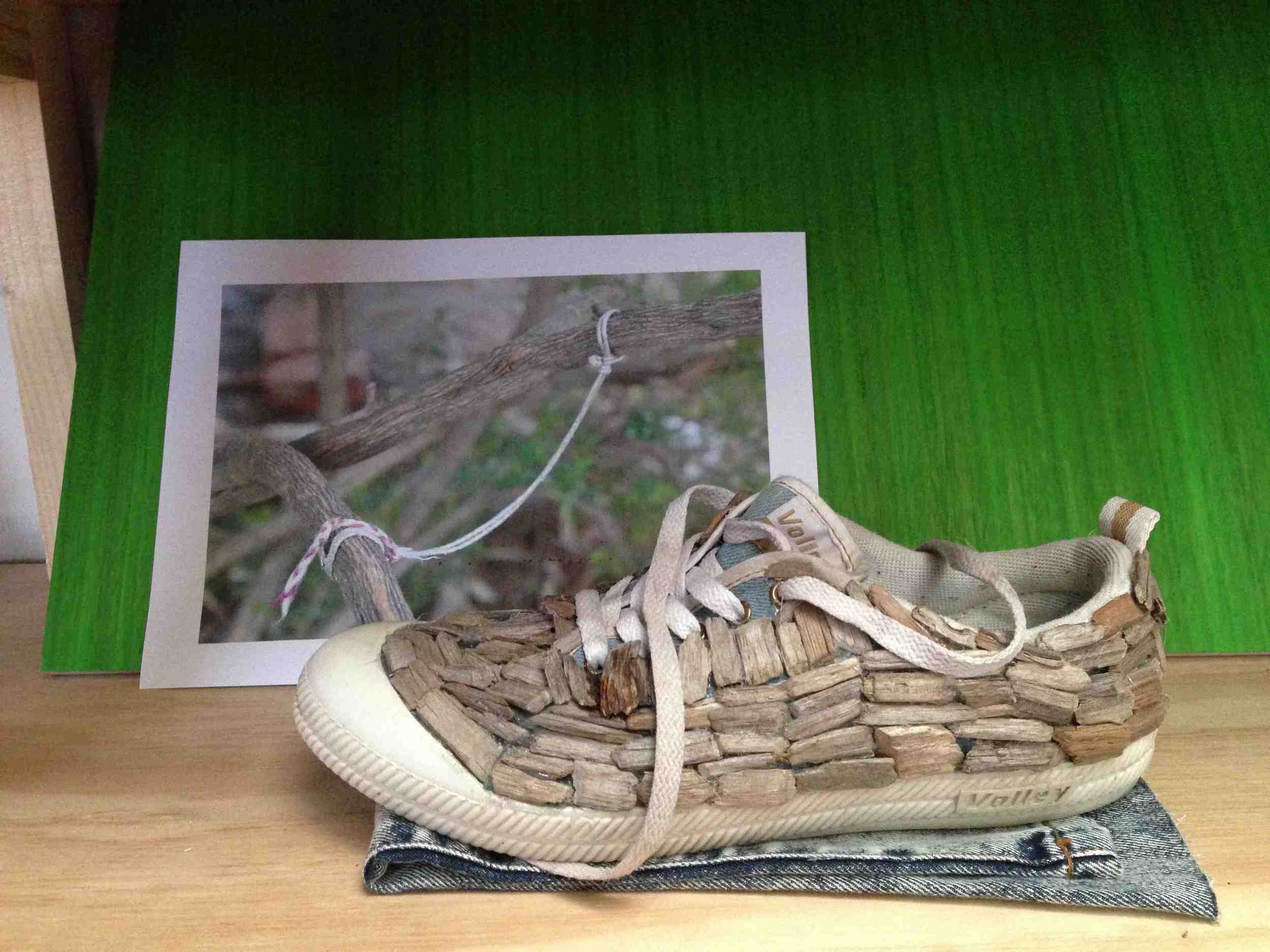

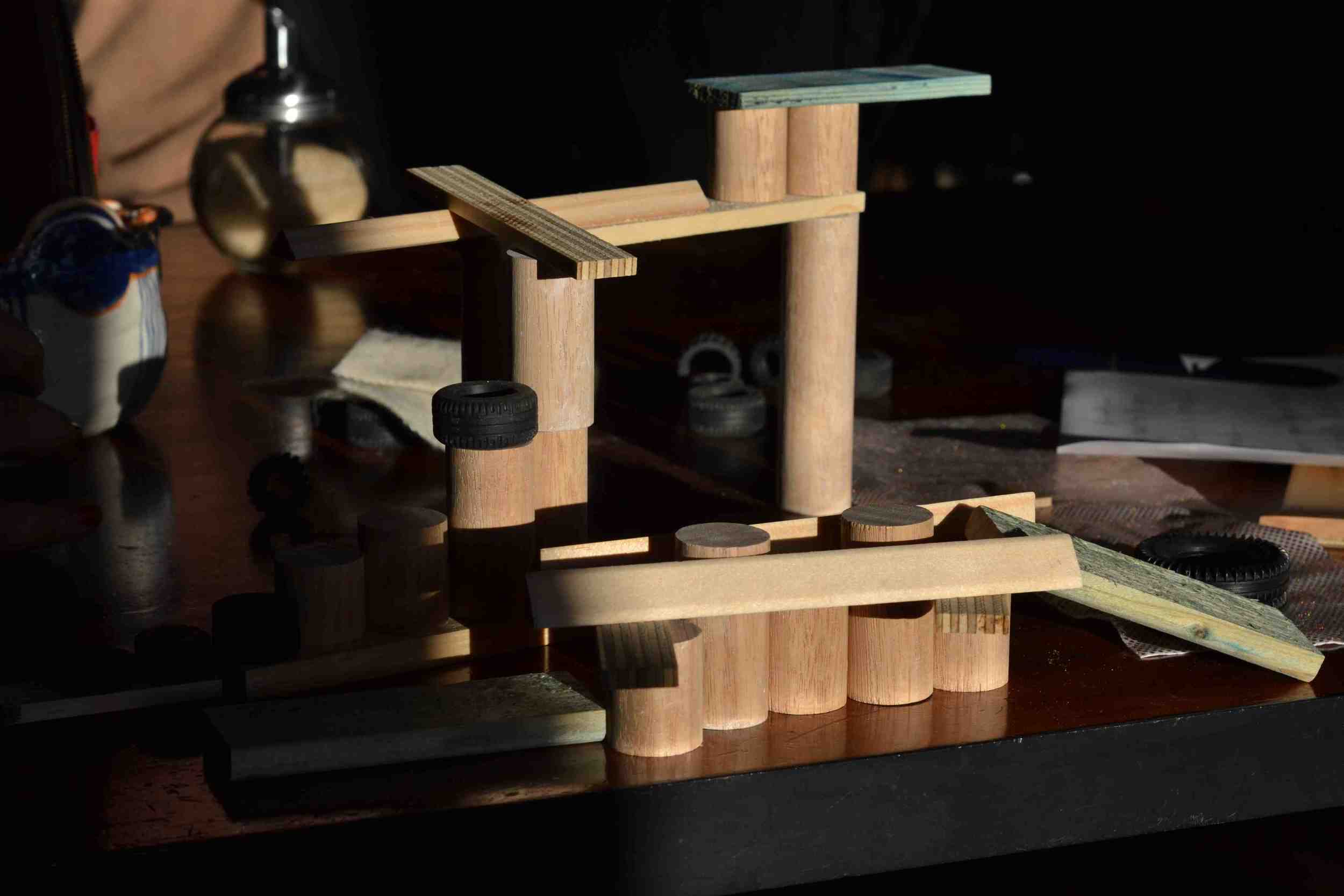

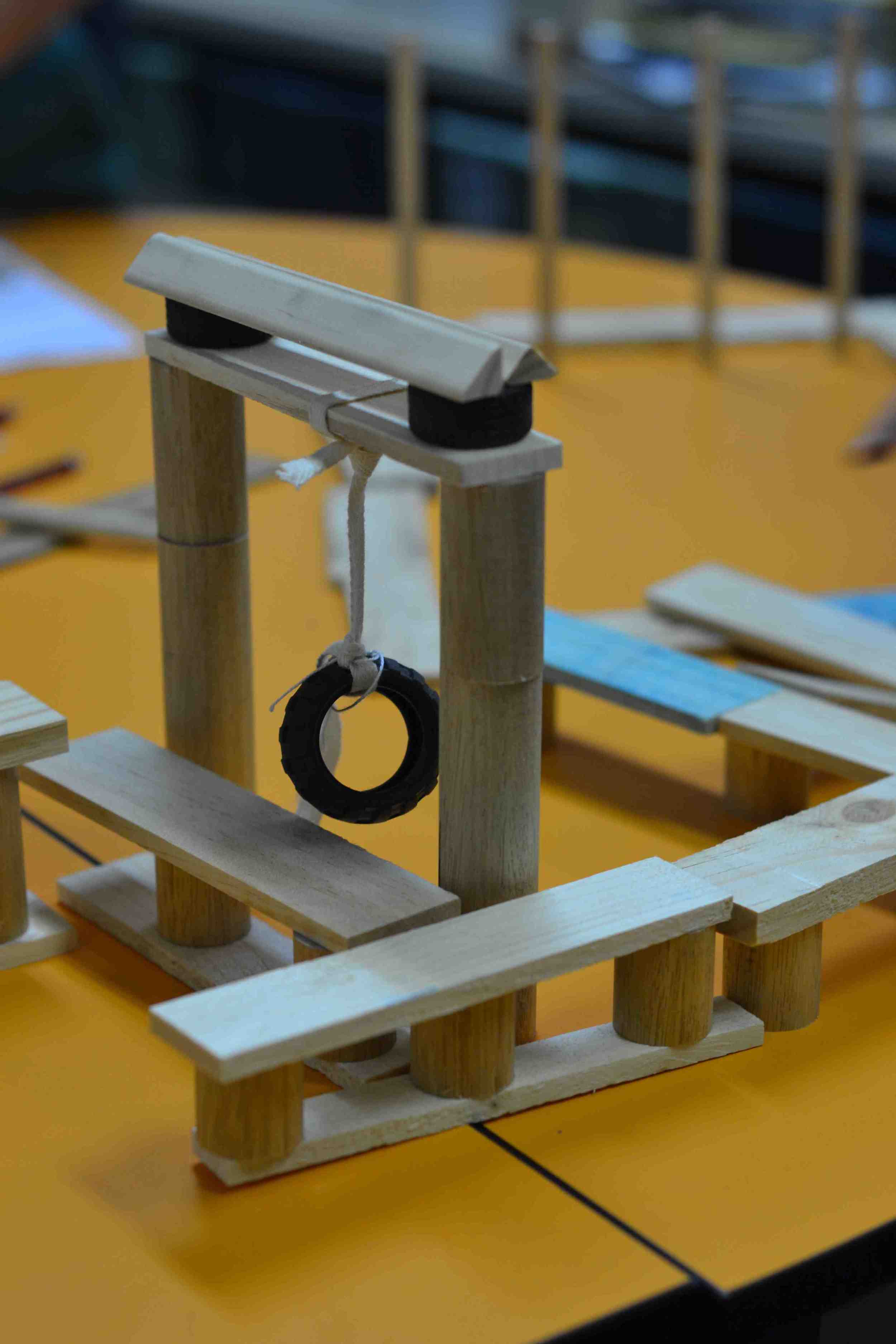

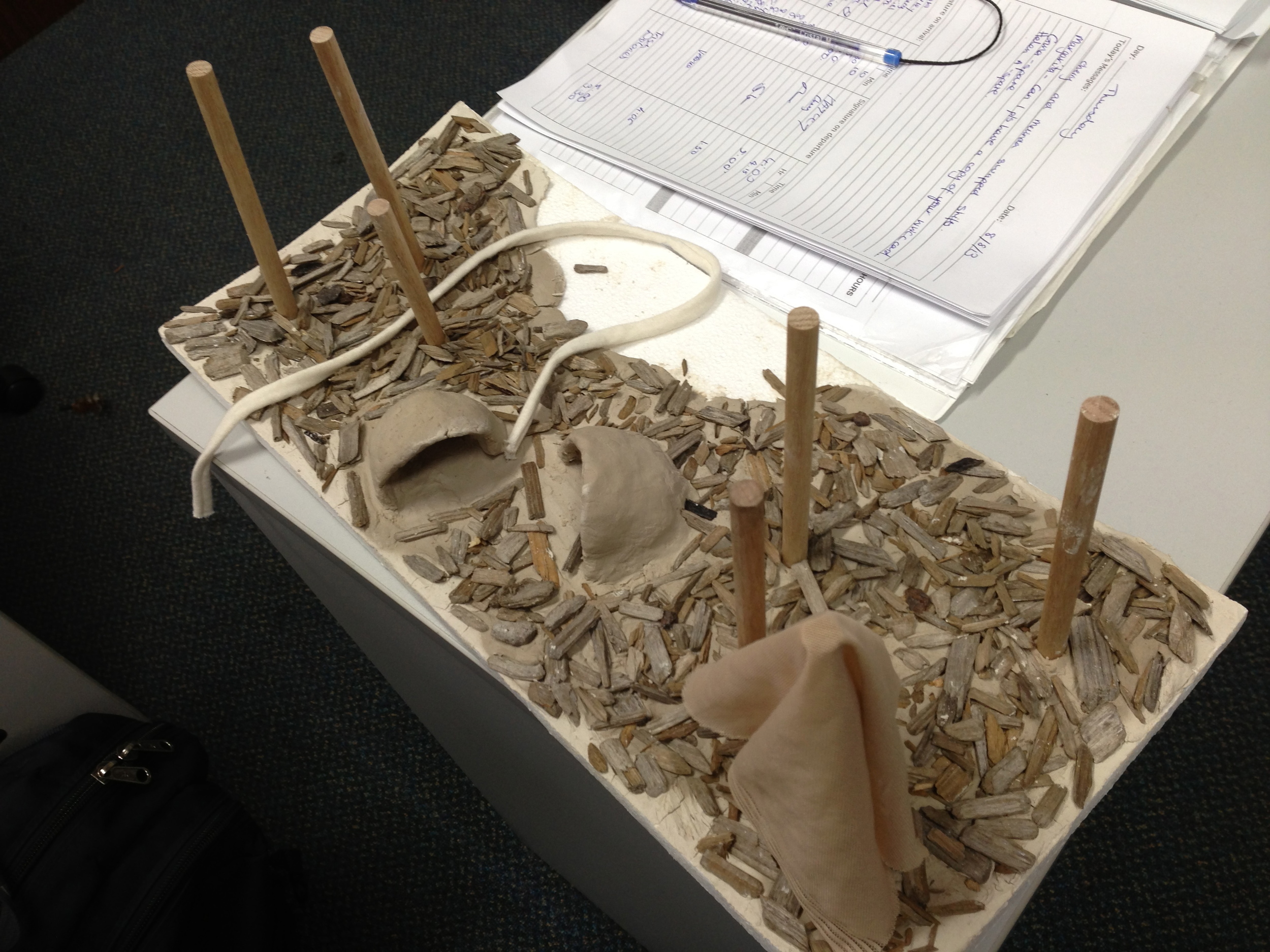

The GOODWILL KIT was designed in March, by April and May it was used in 2 educational centers, an early childhood center and a primary school. In June I invited adults and families to engage in play and set up the kit at Small Block Café and Perimeter Books. Designed for individual use, to create miniature playscapes — the KIT resembles a child's wooden toy box full of tactile inanimate objects, such as lego-tyres, dowels, planks, lengths of string and fabric. Participants are asked to built play spaces that are open and inclusive and while doing this ponder on experiences of play, either current or as a child.

The design, concept and production of the GOODWILL KIT is based on David Cashman and Roger Faginʼs work from the late 70’s, the Islington School’s Environmental project (U.K) the photo documents students work at Laycock School, in Inslington. University lectures’ Fagin and Cashman agreed art students became insular and competitive, and devised an, artists-in-school to collaborate on outdoor play design. Their kit design (in which GOODWILL is based) helped open dialogue. By observing play with the introduction of new platforms, people’s perception of play was transformed and the yard acknowledged as creative site for social forms of learning.

Why focus on play? Roger Caillois’ description of the primal aspects of play as an: ‘...attempt to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict a kind of voluptuous panic on an otherwise lucid mind... Surrendering to a kind of spasm, seizure or shock which destroys reality with sovereign brusqueness.’

In this instance, I employed the use of a toy kit to help define the importance of the unanticipated moments of which play is channeled through the arbitrary. Additionally the kinesthetic object tinkering developed a bi-product release of personal stories, narratives from the sub-conscious that reveal prior experimentation, trust and conflict. This unassuming openness or release became a focus for the project (and continued through the commissioning of private interviews, for film script development). That is, the GOODWILL kit’s intended use helped participants vocalize the socio-political, psycho-spatial conflicts that occur when ideals, desires, beliefs and rights are challenged, that, in some Freudian way manifest in our adult selves. Revisiting embedded sensual experiences of past and how they re-present the present was one ambition of the project. Somewhat this aligns with the avant-gardes’ destruction of meaning and value and their ushering in of art in the psychic arena: for example, Andre Breton’s declaration ‘the mind which plunges into Surrealism, relives with burning excitement the best part of childhood’.3The best part of childhood for participants often excluded those parts harder to acknowledge with strangers.

The project is informed by but not aligned to Joseph Beuys' Social Sculpture practice. Social Sculpture has been described as 'art's potential to transform society' (wikipedia, accessed 22nd of August): As an artwork it:

Includes human activity that strives to structure and shape society or the environment. The central idea of a social sculptor is an artist, who creates structures in society using language, thought, action, and object.

Beuys was confident in his utopian belief, the potential for art to bring about revolutionary change. The Goodwill project differs from this Utopian ideal looking to heighten personal action response acknowledging our propensity take ownership over things, ideas and success while being quick to disown failure. It seeks to use the smallest of objects as metaphor for the politics at play in public or near public space, as when objects free to use are introduced, negotiations take shape in light of learning of an objects capacity for construction, negotiations can alter when observed along with confidence. Particularly when children play with objects ownership becomes a natural part of play although there is no means in which they earn the right to own a free object, whereas adult play is more aware of the politics of ownership and manage their play with this in mind.

It may affect the behaviors of participants when play is documented (some after affects referenced in the 'extinction warrior' project). Rather the focus is on the dialogue between participant and artists creating an opportunity to discuss early experiences of unsupervised play, revealing in discussion the decisions we make and how we chose to interact. Predominately either aggressive or passive, passive- aggressively or violently interacting with each other, objects, space and danger It’s the personal politics (values, ethics, aesthetics) we bring to these environments that forms the interaction (outlet) of experiences bridging our understanding of ourselves (our becoming) through play.

(Roger Caillois, Man, Play and Games, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2001 [1958], p. 23.)

Goodwill Text Introduction by Helen Hughes

Kym Maxwell is an artist, teacher and thinker whose work within and across these distinct fields concerns notions of education, play and social spaces. More specifically, Maxwell’s work concerns the types of interpersonal relationships that are generated by the teacher–student dialogue, and the ideologically unfettered “play” of children.

She is interested in how alternative educational models (such as those proffered by the post-war Italian Reggio Emilia approach) and different types of objects and spaces (such as toolboxes and playgrounds) depart from conventional, top-down models of teaching and nurture new modes of learning instead.

Put more simply, Maxwell is concerned with the intersection between social relationships (student–teacher, student–student), and sculpture and installation (objects and environments used for learning). As such, the physical layout of a schoolroom — its desks, blackboards, and instructional posters — becomes a rich text that Maxwell can mine for invisible elements, like informational flows and interpersonal dynamics or hierarchies.

She continues these explorations in her latest project, GOODWILL, which has involved Maxwell creating a small sculptural “toolbox” and depositing it for general use in two education centres, a bookshop and a café over the course of the year 2013. This book documents and maps their use.

A theoretical toolbox for interpreting what follows, then, might include:

Jacques Ranciere’s account of the French school teacher Joseph Jacotot in The Ignorant Schoolmaster

Irit Rogoff’s e-flux essay ‘The Educational Turn’

Claire Bishop’s chapter, ‘Pedagogical Projects’ in Artificial Hells

Paul O’Neill’s Curating and the Education Turn

Kym Maxwell, ‘Experience and perceptions of “children’s research” and the educational turn’ in un Magazine, 7.1

Joseph Beuys’s idea for a free university

Annette Krauss’s Hidden Curriculum

Palle Nielsen’s The Model for a Qualitative Society

And it is to this broad and important dialogue on the intersection between education and contemporary art that Maxwell contributes, through both her written and artistic practices.

Helen Hughes, 2013.

__________________________________________________________________________________

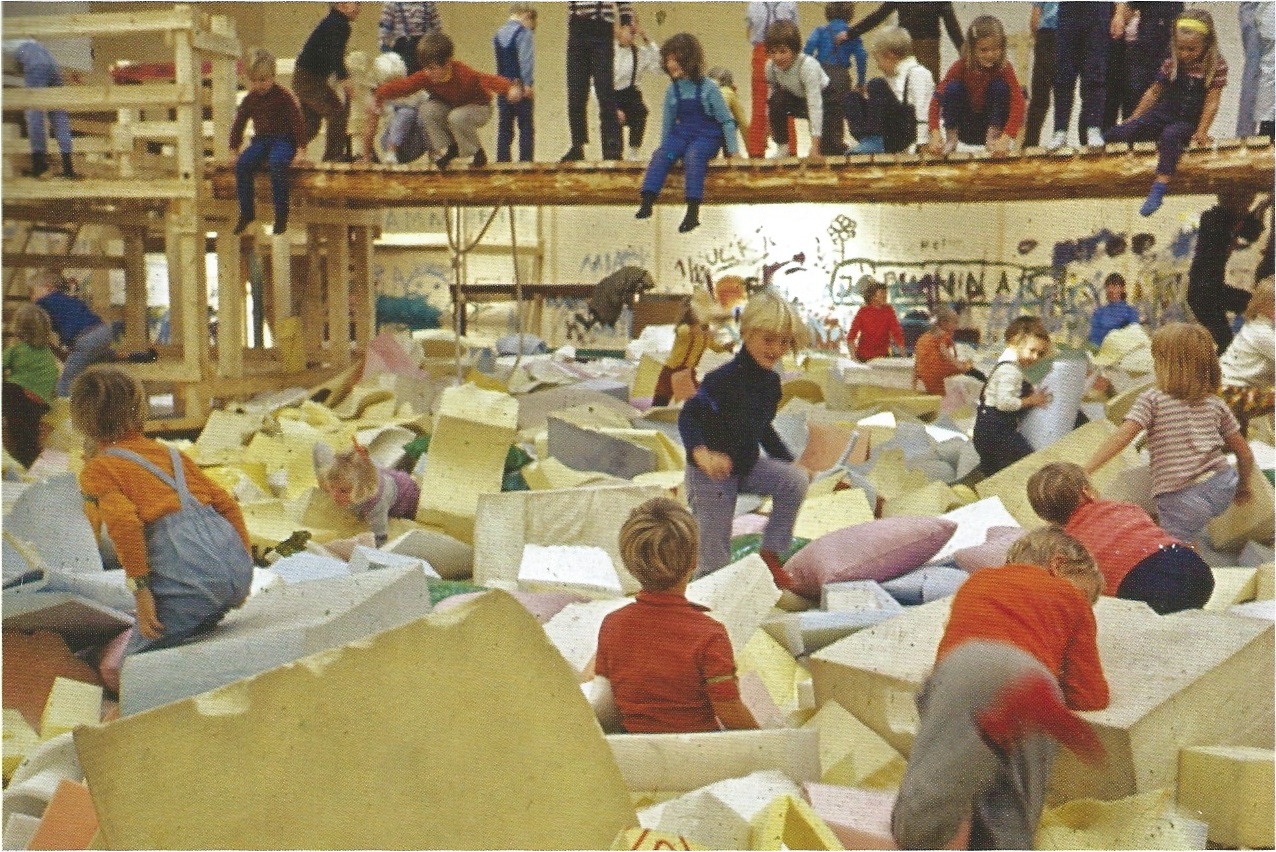

This is an image of Palle Nielsen's 'Model for a Qualitative Society'.

One inspiration is Palle Nielsen’s participatory art of the 60’s and 70’s. Nielsen, a Danish artist who was renowned for his participatory social movement, ‘Action Dialogue’ which built adventure playgrounds in the middle of housing estates in Denmark (1966-1972). This movement inspired a group of volunteer activists to gather a large variety of loose materials (I imagine ex-construction site materials) to create adventure playgrounds for children in areas that had no facilities for outdoor play, at the time the distribution of funds by the city was based on demand. Palle’s approach overstepped this process to make a statement. Sites were created for children’s play and for community gathering. Lars Bang Larsen states:

Nielsen soon took his research onto the street. During one Sunday in March 1968, activists and residents erected an adventure playground, designed by Nielsen, during a raid on the back yards of some old working class housing in Copenhagen’s Northern Borough. Residents were woken up at seven by activists who told them that their backyard had been selected to be the site of a new adventure playground: a roll call that convinced residents to spend Sunday morning building a playground (and not call the police). To Nielsen and his fellow activists, building illegal playgrounds was an alternative to protest forms such as demonstrations or squatting, and aimed at offering a constructive critique of city planning.

Around the same time as the Situationists, Palle’s movement too was aligned with Art Activism dialogue. TO demonstrate his beliefs he bravely asked the Stockholm Museum Moderna Museet’s to initiate one of these playgrounds within the Museum gallery. Over 3 weeks in 1968 ‘Model for a Qualitative Society’ happened. It was one of the largest attended exhibitions at that Museum. Birgitta Arvas wrote: (the museums children’s outreach worker to Palle, Stockholm, 25 November 1980).

It is one of the most important events in the history of the museum – it was, so to speak, the starting signal for a whole new form of organisation, not only at the Moderna Museet but also in most other museums in Sweden.

It is a social act 'engage art' model. In the foyer CTV monitors projected footage from inside the playspace ‘gallery’ to the cafe. Some people chose to watch from a vantage point while others chose to participate, those inline had an alternative playground designed outdoors. Schools appeared and all ages were involved. Acts included painting directly on the wall, hammering, kids DJing and people of all ages jumping from large heights into the foam pit below. There was a famous photo of the town Mayor in full flight jumping into the foam pit.

This was the end to Palle’s work as an artist he perceived the Model too bourgeois, a failed attempt to raise the issues he had intended and it became a focus on the fetishizing of play, without the follow up emancipation that comes from listening and observing he had hoped for. A jolting of reality to embrace.

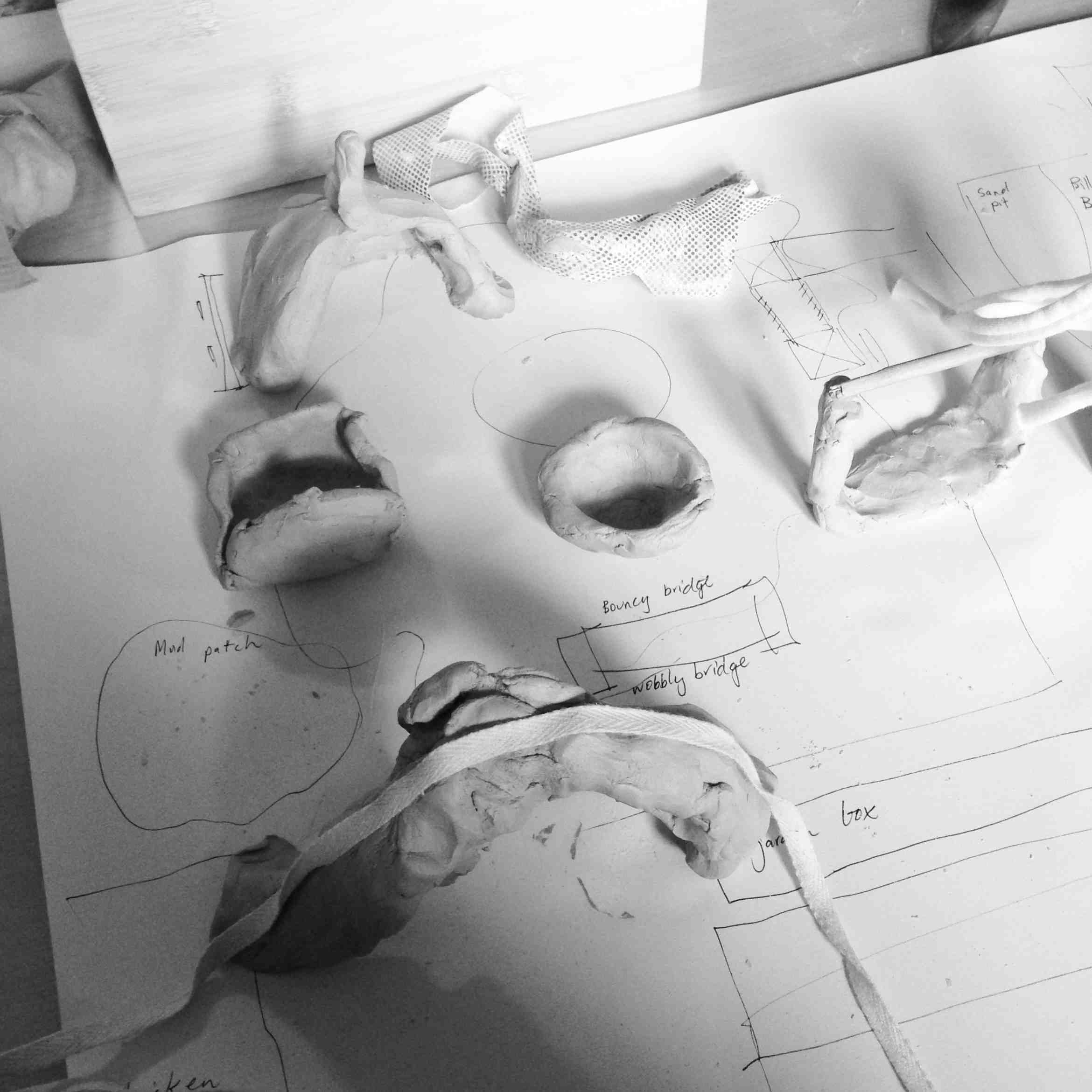

ABOUT CHILDREN’S CENTER IMAGES —

Recent work at the Children's Center has resulted in the building of a playground motif. The materials used for children designs were slightly different than adult designs, the materials reduced down to dowels, clay and fabric. Clay was introduced as the children talked a lot about hiding so we considered introducing it so that they may create caves. The staff and I thought these studies would transfer well to concrete sculpture designs. I showed children evidence of their previous designs discussing the main themes as 'hidden places’ where faces or bodies are concealed, and 'standing straight dowels' for a ‘tree forest’ (term developed in consultation with the landscape gardener) and 'caves'. We discussed filling the cave with grouted in mirror. The reflective surface can be played with, with natural light and torches. Each idea was children initiated.